Almost every health official, physician or researcher you speak with will agree: COVID-19 testing among every population is essential for informing virus detection, self-isolation, and prevention of onward transmission. Racial disparities related to the COVID-19 epidemic and the associated public health response continue to be discussed, but need further study to understand the modifiable driver of these health inequities.

One research team, lead by Institute for Public Health Faculty Scholar candidate, Aaloke Mody, MD, assistant professor in infectious diseases at the School of Medicine, is using a well-established tool to measure disparities in COVID-19 testing among Black and White populations. Taken from economics, the “Lorenz Curve,” is a way to graphically represent distribution equity of a resource (like a test or vaccine) across a population.

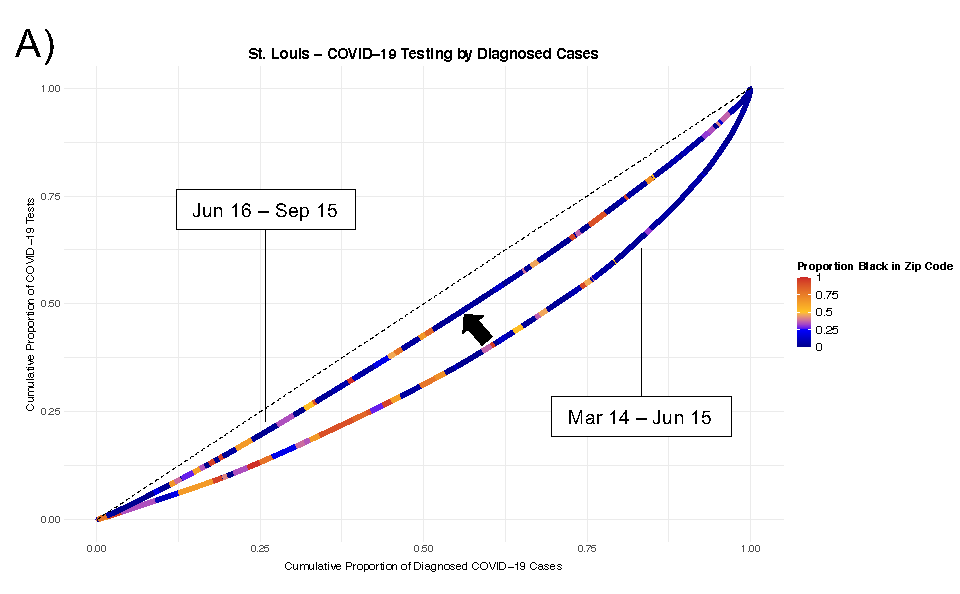

Figure A: Lorenz Curves of Disparities in COVID-19 Testing. This figure depicts modified Lorenz curve examining disparities in COVID-19 testing. The units of analysis are zip codes and they are color-coded by their overall racial makeup. Separate curves were generated for the periods between March 14 to June 15 and June 16 to September 15. The dashed line represents equitable distribution where 50% of testing would be conducting in zip codes accounting for 50% of hospitalizations. Panel A depict Lorenz curve measuring disparities in the distribution of COVID-19 tests relative to the diagnosed cases in a zip code for the St. Louis region.

Mody’s team studied data from the Missouri State Department of Health and Senior Services on COVID-19 tests conducted among Black and White populations in both St. Louis and Kansas City.

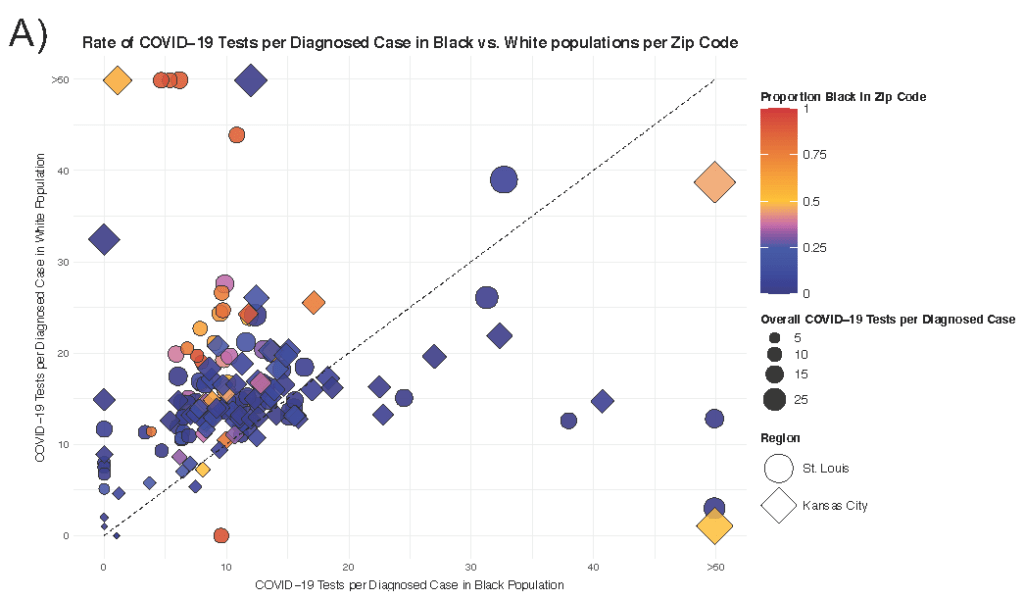

Figure A: Disparities in COVID-19 Testing Among Black and White residents of the same zip code. This figure depicts testing rates per diagnosed case in Black versus White residents of the same zip code. Each marker represents a single zip code in the St. Louis (bubble) or Kansas City (diamond) region. Markers are color-coded by the racial makeup of the zip code and sized by the absolute rate of COVID-19 tests per case. The dashed line represents equitable testing distribution between Black and White residents. Zip codes falling above the dashed line in Panel A or below it in Panel B indicates that they decreased testing in Black as opposed to White residents (and vice versa).

Dr. Mody explains, “In our case, if testing was equitably distributed, the Lorenz curve would follow the 45 degree line; the more convex the curve becomes, the more inequity there is.”

Mody says that disparities in COVID-19 testing remains underexplored. “Adequate COVID-19 testing is essential for early disease identification and self-isolation, and is an essential tool for preventing onward transmission, but has also been one of more limited resources, particularly early on in the epidemic” he says. “We looked at the number of COVID-19 tests conducted per diagnosed COVID-19 case, as this helps us understand how adequate testing is in an area (i.e. if there are more cases in an area, there needs to be more testing.)”

The study produced several key findings:

- Black populations had consistently lower COVID-19 testing rates per diagnosed case compared to White populations in the two Missouri regions.

- Despite increases in testing over time, disparities between Black and White populations were persistent throughout the Spring and Summer of 2020.

- Testing disparities were consistent in both the St. Louis and Kansas City regions.

- Testing disparities were persistent across zip codes in each region, with lower testing rates in zip codes with a higher proportion of Black residents.

- Even within the same zip codes, testing rates were lower among Black residents compared to White residents.

As a result of these findings, Dr. Mody’s team concluded that when the disease burden is higher, testing also needs to increase to make sure health practitioners are doing a good job of finding both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases.

The team also surmised that proactive public health strategies that really help to ensure equitable testing are needed, such as making community-based testing widely available. This is currently happening across both regions.

And finally, the study found that disparities are not static. They can change over time and should be monitored. Dr. Mody says the methods used in this study “provide a relatively straightforward and useful metric to track how equitable public health programs really are.” This is particularly important to track inequities for the resource that is currently in shortest supply—COVID-19 vaccinations. Read the study.